‘Trial’ writer Leslie waives her right to remain silent

Bridgit Brown

What if Mammy jumped out of her television caricature and became human? Playwright Karani Marcia Leslie poses that question in “The Trial of One Short-Sighted Black Woman vs. Mammy Louise and Safreeta Mae,” now playing at the BCA Plaza Theatre at Boston Center for the Arts.

The play tells the story of Victoria, the title’s “short-sighted black woman,” who decides to take two longstanding unfavorable stereotypes of black women — the jovial, asexual and servile Mammy and the hyper-sexualized and Jezebel-ish Safreeta Mae — to court for promoting what she feels are negative images that have impeded her ascension up the entertainment industry’s corporate ladder. Throughout the staged trial, Leslie takes both characters and audience through a journey of complex human emotion with compelling testimony as history confronts the present.

Full story

|

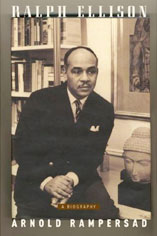

Ralph Ellison: A literary giant unveiled

Darryl Lorenzo Wellington

Ralph Ellison was only three when his father died, leaving him the fatherless son of a cleaning woman in segregated Oklahoma. By the time of his death in 1994, he was counted among the giants of American letters. Yet after achieving success in 1952 at age 40 with his masterpiece “Invisible Man,” Ellison’s subsequent publications were few and his public persona reserved.

When we think of Ellison today, it is as a class act. He stood for high standards in his craft, belief in a unique African American culture, and the conviction that all racial and ethnic identities were subsumed by a noble American heritage.

After “Invisible Man,” Ellison shrouded himself in the garb of high art, discoursing on literature and jazz, even as he downplayed the influence of sociology and race in creative accomplishments. Faulkner declared Ellison was not “first a Negro, but first a writer.” Ellison seemed to embrace the words. He was an artist first; second, an American; last, a Negro. It is not surprising that Arnold Rampersad’s excellent new biography “Ralph Ellison: A Biography” reveals the dents in Ellison’s armor. Full story

|